Panel Parity – what we achieved, and how we did it

Posted: May 6, 2013 Filed under: gender parity, programming | Tags: gender parity, programming 1 Comment(This was originally posted on 6th May, and an amended and extended version was posted on 8th May).

Just over a year ago I wrote a blog post explaining why Eight Squared Con was committing to gender parity on panels and what we meant by that. We said that we would seek to avoid panels where one gender was in a minority, and would do so by aiming to have a sufficiently large pool of programme volunteers that itself represented the broad gender parity seen at Eastercons in recent years.

So, how did we do?

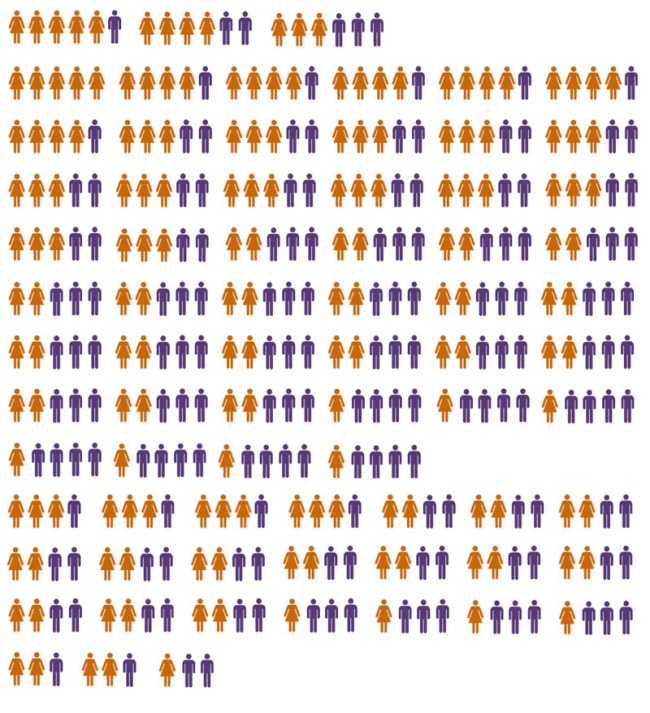

This graphic depicts all our multi-person panel items. In other words, it doesn’t include single-speaker talks, two-person interviews, or ‘event’ items such as opening and closing ceremonies. That leaves us 73 panels that we consider we were seeking to achieve gender parity on.

In numerical terms:

- Of the 3 6-person panels, one was balanced; the others were predominantly female.

- Of the 46 5-person panels, 32 were balanced. 6 had one man and 7 had one woman; one was all female.

- Of the 21 4-person panels, 13 were balanced. 4 had one man and 4 had one woman.

- All 3 3-person panels were balanced.

Now, one of the first things to observe is that although we achieved gender parity, we didn’t quite do it the way we originally envisaged, i.e. by having as equal as possible a gender split on each item. (By ‘equal as possible’ I mean that changing the gender of one participant would not affect the overall balance. So a 5-person panel is balanced if it has a 2:3 or 3:2 split; a 4-person panel only if it has a 2:2 split.)

In practical terms, it became clear that this would be extremely difficult. Even with a very large pool of participants, as discussed below, there are some topics where you have more prospective panelists of one gender than of the other. Equally, there are practical constraints such as avoiding programme clashes or times when a particular person isn’t available that have to be taken into account. Some sorts of items are harder to assemble a panel for, either because there are few people attending the convention with those particular interests, or because certain sorts of item (in particular, those with an element of performance, such as panel games) attract fewer volunteers.

However, there is another way of looking at gender parity that is, I suggest, as valid or perhaps even more valid than parity on each item. That is striving instead for a programme that is no less gender-equal than one where the panelists had been selected from an equal pool of men and women without any consideration to gender at all.

One can calculate the statistics for this (hands up if you remember the binomial theorem). If we’d allocated in this manner, we would have expected 29 of our 46 5-person panels to be balanced, and 2 or 3 of them to be all-male or all-female. Instead, as noted above, we did rather better than this, with 32 balanced panels and only one single-gender one. For our 21 4-person panels, we’d have expected a random allocation from an equal pool of men and women to result in only 8 balanced panels, and 2 or 3 to be all-male or all-female. In fact we had 13 balanced panels and no single-gender ones.

Moreover, if you count panel slots (i.e. seats on panels) we had a total of 341; this is a bigger number than our number of programme participants (190) because many people were on more than one item. Of those 341 slots, 169 were filled by women and 172 by men.

So, in our view we succeeded in our overall aim. The programme was balanced in terms of the number of male and female participants, and the majority of individual panels (49 of 73) had parity. We could not always avoid panels with a single man or woman, but we only had one single-gender panel. Above all, we had more gender-equal panels than would have been expected by a truly gender-blind allocation from equal numbers of men and women.

How did we achieve this? In large part by doing what we intended and getting a wider pool of participants than has tended to be the case. With 190 people on programme, we had about a quarter of the adult attending membership taking part. Given that the overall attendance at Eight Squared Con was about 40% female, our programme participant pool was also fairly evenly split. We made every effort to reach out to potential programme participants, and used a detailed volunteer form to ensure that we had as much information as we could about our volunteer’s interests and the sort of items they wanted to be on.

Now, this discussion has all been in the context of panel parity. I said earlier that I’d excluded programme items with only one or two participants. But there is one area outside panels that we should acknowledge we could have done better on, and that was on individual talks. Setting aside those talks arranged by other bodies, and Guest of Honour items, we had four items presented by a single speaker. All four of those speakers were male, and if I was looking to move beyond just panel parity at conventions I’d seek to ensure that we made sure that men and women were more equally represented on talks too.

Overall though we had a lot of feedback at and after the convention suggesting that we’d managed to run a varied, full and diverse programme that attained the high quality standard we’d set ourselves. Indeed, by making us look more carefully at the composition of each programme item, and by leading us to go out and find as wide a possible pool of participants, we believe that striving for panel parity actually improved the quality of the programme as a whole.

[…] Panel Parity – what we achieved, and how we did it […]